ShowBusinessMan:

YouTube

Mood Today: Blue Velvet

Britney Video Awards 2012 Promo Video

YouTube Blog: Ads that entertain: YouTube’s top spots of 2011

Top 10 Most Viewed Videos on YouTube for 2011

2012 The Year In Review "Rewind YouTube Style"

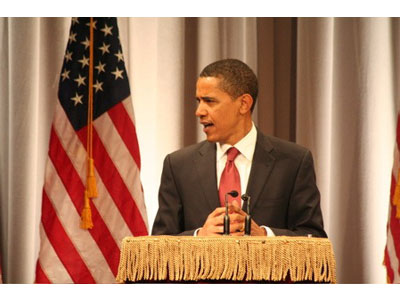

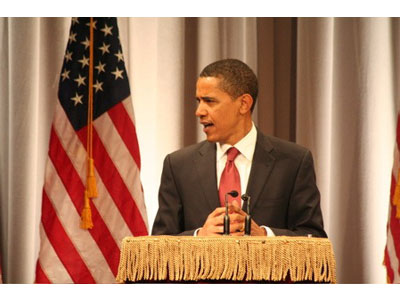

Obama has told to teenagers about dangers Facebook

The White House will not influence decision GM on sale Opel

Reform of US Public Health

To reach to...

Very oppositely, but it's interesting

Not bias

The Red Face