ShowBusinessMan [Search results for Egypt]

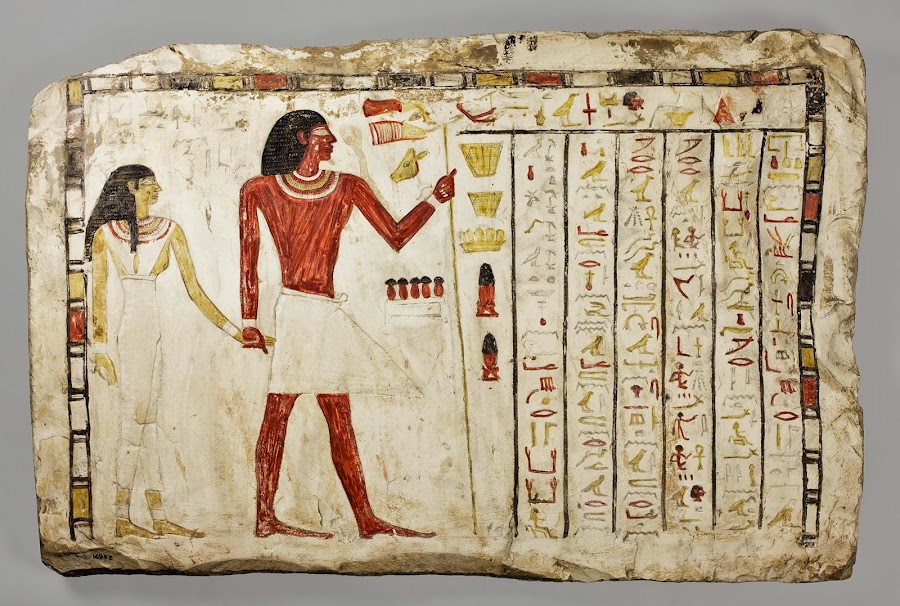

Exhibition at Oriental Institute shows how ancient cultures commemorated the dead

The myth of Cleopatra at Pinacotheque de Paris

Illustrated Tweets by Coca-Cola Egypt — IBA Painted

The horse: from Arabia to Royal Ascot at The British Museum

Etisalat First Android Smartphone Triggers Mobile Destruction